Contact Information

- Management: johndkastner@gmail.com

- Press - US: jo.murray@gmail.com

- Press - UK: steve@carryonpress.co.uk

- Booking - US: rfraser@wmeentertainment.com

- Booking - International: andy.cook@caa.com

Bio

Some people will call Songs For Our Mothers the most unpleasant album of this year, if not of their entire generation; the work of a bunch of drink and drug wracked nihilist degenerates. Some will say that it is a thrilling statement of disgust, defiance and complete creative independence made by the only rock band in the UK that really counts for anything at all anymore. But it is likely that few who hear it will walk away from the second album by the Fat White Family, released on their own label Without Consent, not caring one way or the other.

Some will hail this hair-raising, pulse-quickening and indignant collection of glitterball disco, smacked out psych, glam funk, heart-breaking torch songs and otherworldly slabs of Kraut n’ western as the shot in the arm that independent rock has been ailing after. And a shot in the arm is exactly what this album is. For if modern indie rock, DIY, alt-country – call it what you will – is sick, then the Fat Whites are the pretty nurse with Munchausen’s Syndrome by proxy, pushing down the plunger on the syringe; murdering the bed-ridden patient with a tainted injection right under everyone’s noses. They have witnessed an entire musical scene teetering on the verge of terminal irrelevancy and given it a hard shove void-wards.

And the dark irony is that physically, mentally and psychically the band nearly disintegrated themselves long before they got chance to deliver the goods. After working so hard on the band for so long, when it looked like their time was finally here, frontman Lias had no intention of letting three serious illnesses one after another stop them from having their moment. “I had pneumonia and was coughing up blood at one point… I thought I was done for”, he says, “It was a result of snorting and drinking every day and living at the Queens [their one time Brixton pub HQ] but then instead of recuperating going out on a really long tour and ending up in a really bad way.”

And no wonder some of this sickness and deathliness has saturated the new album. Those looking for dark, subversive, thrilling, transgressive (and sometimes satirical) art that unwaveringly holds a mirror up to the morally blank times we live in will find what they want in the Songs For Our Mothers; just as those who revel in being offended will do likewise. It’s hard not to wonder – especially when you look at some of the song titles (Love Is The Crack? Goodbye Goebels? Leibensraum? When Shipman Decides?! Hoooo boy: they’ve pushed the boat out this time!) – if the band are just handing ammunition to perma-outraged liberal detractors who will inevitably call them fascists, advocates of hard drug use, serial killer fanboys (among many other things) instead of looking for deeper meaning.

Lead singer and lyric writer Lias Saoudi grins: “Yeah, and we’re handing them the ammunition gladly… because people who get up in the morning to look for Nazis end up seeing them everywhere by lunchtime.”

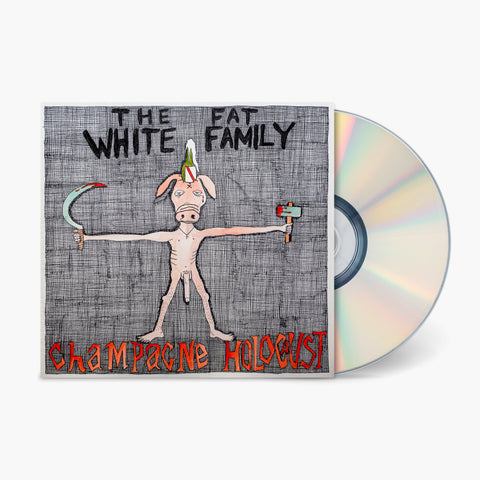

Lead guitarist and music writer Saul Adamczewski is deadly serious when he adds: “I think what I learned from our debut Champagne Holocaust is that if you were going to listen to all of your online critics it would pretty much be impossible to do anything other than toe the line completely and make the most conservative music imaginable. We’ve already been called fascists. We’ve already been called Stalinists…. So what do we actually care? And besides, these are the best questions to ask and the best scenarios to explore. Who cares about the artistic potential of singing about good people and good situations?”

Before Lias adds laughing: “So we just thought we might as well crank it up to 11.”

But if the album nearly didn’t happen because of illness, it also nearly didn’t happen because of Saul and Lias’ obsessional idea of what the band should sound like. Scores and scores of songs were scrapped and several recording sessions were abandoned because the music just wasn’t sounding exactly right; and that was including one attempt to make the album at new pal Sean Lennon’s studio in Woodstock. Saul says: “I’ve met a lot of people since the last album… the millionaire set, the sons and daughters of famous people, and most of them are horrible but Sean’s really sound. A nice guy. We’ve become good friends.” (One track from that session did make it onto the album however, Satisfied, which is about “the vertigo, or fear of sex” and involves the unlikely scenario of receiving oral relief from revered literary titan and holocaust survivor, Primo Levi.)

But it wasn’t until the band returned to England and decided to throw disco into the mix that the project really took off. Saul says: “We’d been playing ‘The Whitest Boy On The Beach’ live for ages but it wasn’t until we tried it in this Giorgio Moroder producing Donna Summer style that I realized we had something that we could use.

After we finished the last album two years ago we were convinced it had been a massive waste of time so we ran away to Spain to become buskers. We went to live on a beach in Barcelona for two weeks. It was so hot we were hiding in this tiny bit of shade, just cowering away from the sunlight. And there were 12-year-old boys with muscles and beautiful girlfriends, just striding round in the heat. And we were just pathetic; the weakest links in the chain, as the song says.”

The song mixes together the aesthetic of Throbbing Gristle (Lias, Saul and organist Nathan took a trip up to Beachy Head to recreate the cover for 20 Jazz Funk Greats for the single cover) with a sound that owes as much to the Sparks as it does to Donna Summer as it does to Naffi Sandwich (while still finding space to throw in a reference to TS Eliot’s ‘The Hollow Men’).

There is a theme of abusive relationships that runs through the album – a metaphor for Saul and Lias’ fractious but creative relationship. “I guess I am a bit of a masochist”, sighs Lias. “And that’s just as well because I’m definitely a sadist”, says Saul. “There are only so many times you can have a tambourine thrown at your head before you start imagining you’re in the bunker with Hitler or that you’re Tina Turner”, adds Lias, only partially joking.

One of these songs ‘Hits Hits Hits’ was inspired by an attempt to unpick the creativity from the violence in Ike and Tina’s relationship. Lias says: “When I got seriously ill I had to go to my dad’s to recuperate and I got obsessed with their story. ‘Hits Hits Hits’ isn’t making light of what happened to Tina Turner – it isn’t necessarily even about them it’s just about the kind of situation you can find yourself in, in a creative partnership. On one side of their relationship you’ve got this amazing songwriting and performing partnership and on the other side you’ve got this horrific domestic violence and these things are definitely connected as uncomfortable as that thought might be. You play a character when you sing this kind of song and if people have trouble with that idea then they really have to question their stance toward art full stop.”

Of course another of these songs, ‘Goodbye Goebels’, finds inspiration from an even bleaker source – the bunker in which Hitler and his last allies in national socialism committed suicide. “This was my idea”, says Saul gleefully, “I came up with the concept as a challenge to us. I asked Lias would it be possible to write our most sincere and heartfelt song ever but about the last few hours in Hitler’s bunker just before they took their own lives. I think the lyrics are beautiful. They’re my favourite Fat White Family lyrics. Regardless of who they were, they genuinely believed in what they were doing and there must have been love in that relationship.”

Lias adds: “The song definitely derived from the situation that had built up around us trying to make this second album. It is a grotesque extension of an egotistical fantasy: the melodies, the memories, the music and what felt like the whole fucking world waiting for us at the door, ready to hang us from meat hooks, just like self-righteous scum like us deserve.”

One of the darkest and most surreal songs on the album is ‘Tinfoil Deathstar’ – a ghost story which deals with heroin abuse and the spectre of austerity victim, David Clapson.

Saul says: “There’s no hiding it, it’s about smoking heroin. It’s become massively popular among young people in London over the last few years. Part of it is to do with getting older and naturally progressing into harder drugs but it’s also to do with people being impoverished. We’re not making a judgement about it, just writing about it.”

Lias says: “A few years ago no one was on it but then this brown cloud rolled through London. The three nights a week on cocaine? No one can afford that any more. At the end of the song the ghost of David Clapson is standing at the window asking to be let into the party. He was a former soldier, a veteran, who had his benefits cut after he missed one appointment and they found him dead in his apartment. He had diabetes and couldn’t afford to keep his fridge on and keep his insulin cool, which was the thing that killed him. He was found next to a stack of CVs… it’s fucking disgusting. He had £3.44 to his name and the autopsy showed he had no food in his stomach when he died. He had worked his whole life and only started claiming dole so he could look after his mum.”

Saul adds bluntly: “It’s just murder. He was murdered.”

Lias concludes: “It was murder. I like how the song sounds really gleeful and upbeat; the idea of having a warm heroin glow surrounding all of these young people having their youthful opiate adventures but right at the end the ghost of David Clapson is outside the room looking in, tapping on the glass with a bunch of CVs in his hand, waiting to be let in. He is like their Ghost Of Christmas Future. These are two separate realities and they may be disparate but they are linked and I was just trying to bring out this underlying link.”

The pair are keen to point out that it is easy for them to fill the vacuum created by the pusillanimous nature of other bands in 2016.

Saul spits: “We really are living through the worst times but that makes it easier for us. I think we’re a good band and I’m proud of what we do but the reason why we get as much attention as we do is that there’s nothing else going on. Some people talk about us as though we’re the best band there is but there just isn’t anything else… especially at the level we’ve risen to. So we’re competing with big indie bands who have signed to major labels like Peace and Slaves but we’ve got literally nothing in common with them. Those bands are just toeing the line and making bland commercial music. What we do is not commercial and it is hard to digest and bracket so it’s not surprising that people pay attention to us.”

Unpleasant or not, the Fat White Family are the last truly great rock band in the world and in Songs For Our Mothers they have created an album that demands to be heard.

John Doran, Utrecht, November 2015

Tracks

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Press the space key then arrow keys to make a selection.